Sequential vs Random

One simple but game-changing insight I had about database query performance was realizing how fundamental the number of sequential and random reads is to the way databases choose query plans, because sequential reads are (far) cheaper than random ones. This difference is easier to grasp if you think about spinning disks: sequential reads simply let the disk spin and stream data, while random reads force the disk’s head to seek a new position to find what you need. This gap is smaller for SSDs, because they don’t have moving parts anymore, but it’s still significant enough to influence how queries run. Recognizing this performance difference—and knowing that indexes are separate structures which often involve seek operations—is, in my view, key to understanding how databases reason about query performance.

This lesson hit me about ten years ago. We had a heavy reporting query that ran every morning against a MySQL replica, usually taking around 10 minutes to complete. One day, though, users started complaining the report didn’t execute. We started the investigation and realized it wasn’t that the query didn’t execute, but actually that it was still running. Overnight, the query time had jumped from 10 minutes to over an hour. At first, thinking it was just a transient issue—perhaps the database was under unusually heavy load during report time—we decided to leave it alone and see if it would sort itself out the next day.

The next day came, and to our surprise, the query was still painfully slow. OK—time to dig in. The first thing we noticed was that the database was doing a full table scan to execute the query, completely ignoring an index we had in place. At first, we weren’t even sure if the index had ever been used—surely the database hadn’t just changed its mind about the query plan overnight… or had it?

It seemed it had. When we ran the query with a FORCE INDEX, the execution time immediately dropped back to the expected 10 minutes. MySQL had indeed changed its mind overnight. OK—forcing the index fixed the problem, but we still wanted to understand why it happened. At that point, with our limited database knowledge, we had two big questions in mind:

- If there’s an index, shouldn’t the database always use it?

- How did MySQL get this so wrong?

Let’s see some answers.

1. If there’s an index, shouldn’t the database always use it?

Indexes in databases are separate structures from the table rows themselves. They make it fast to locate rows that match certain filters, but there’s a catch: after finding those rows, the database still has to “jump” to the actual table data on disk to retrieve the remaining columns. These jumps typically involve random I/O.

Suppose you have a table with 1,000,000 rows and you run a query filtering an indexed column that matches only 10 rows. In this case, the database will use the index—it’s much cheaper to perform 10 random seeks than to scan all 1,000,000 rows sequentially. But if your filter matches 900,000 rows, the story flips. The database will skip the index and just scan the whole table sequentially, because reading all rows in order is far cheaper than jumping around for nearly every single one.

Back to the story: every morning, our MySQL instance was quietly asking itself the same question: “Is it cheaper to use the index to find all rows for the last 30 days and then jump around to fetch each one, or should I just scan the entire table in order?” Databases rely on cost estimates for these decisions, and those estimates are constantly updated as data changes. Up until that fateful day, MySQL believed the index was the smarter path. But then, literally from one day to the next, it decided that a full table scan was the way to go.

2. How did MySQL get this so wrong?

The explanation we came up with at the time for why MySQL made such a bad decision was that its cost estimates were still based on the assumptions of spinning disks (and to be fair, SSDs weren’t nearly as common back then), while our database was running on SSDs. Random I/Os were far cheaper than MySQL expected, which made it believe a full table scan would be faster.

If you’re thinking that MySQL “should do better,” it’s worth reading the PostgreSQL documentation on the

random_page_costparameter to see that things aren’t so simple. Notice how tricky it is to arrive at a reasonable default: the value is set to4.0. According to the documentation, that’s already low for mechanical disks but too high for solid-state drives (where it should be closer to1.1). So why4.0? The docs explain: “The default value can be thought of as modeling random access as 40 times slower than sequential, while expecting 90% of random reads to be cached.”

Some Pictures Worth a Thousand Words

Let’s imagine you have a table with 12 rows, each with a date column, and your goal is to find all rows from July 1st to July 5th.

If you don’t have an index (or if the database decides not to use it, as we just saw), this is what happens: the database scans through all the table rows, filtering out those that don’t match the date range. It’s easy to see how this approach becomes problematic when your table has millions of rows and you’re only interested in a few.

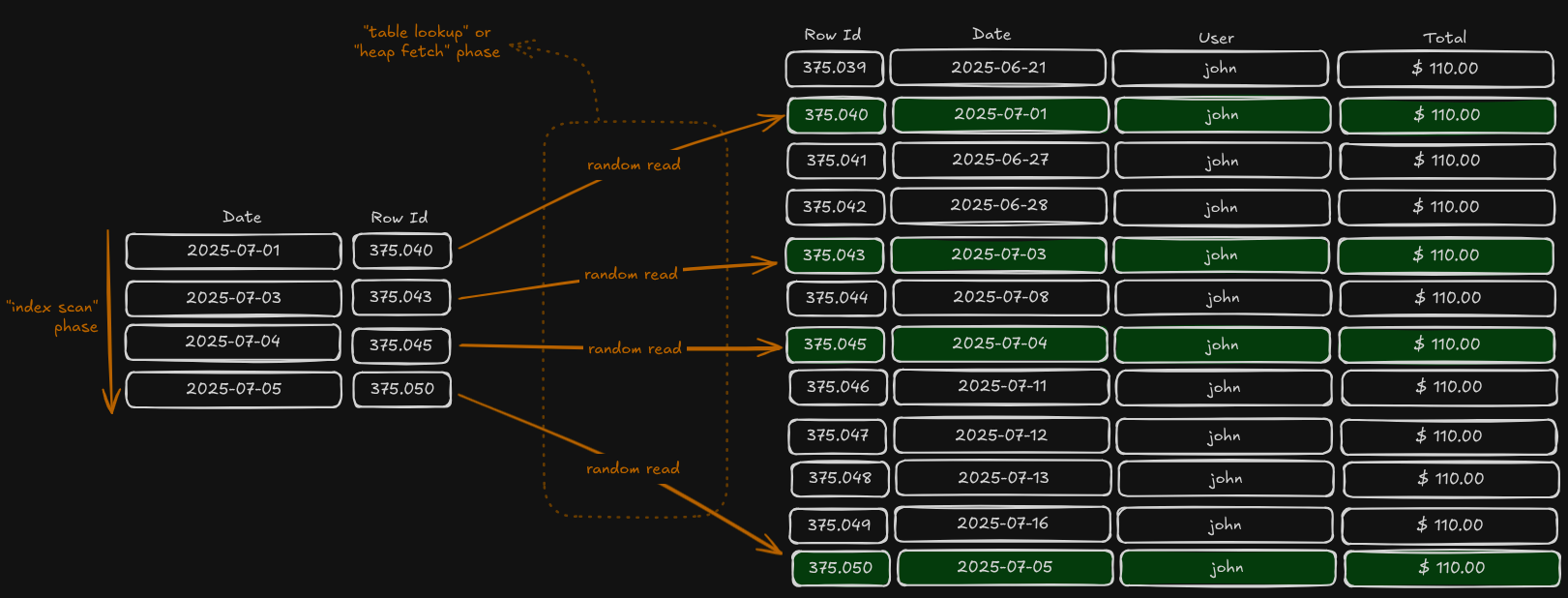

If you do have an index (and the database decides to use it), here’s what happens: the database quickly locates all matching rows in the index, then jumps to each row to fetch the actual data, since the index only stores pointers to the actual rows.

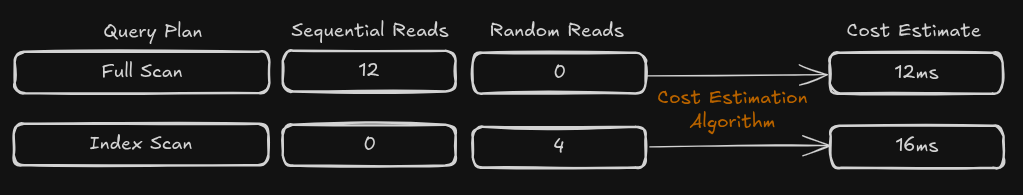

Ten years ago, I thought it was obvious that using any index would always be better than scanning an entire table—“reading 4 rows will be much faster than reading 12 rows” I would say. But here lies the heart of this discussion: not all “reads” cost the same. Because the table’s rows are stored sequentially on disk, reading 12 rows in order is very different from performing 12 random reads scattered across the storage. And in this specific case, even 4 random I/Os can end up being more expensive than sequentially reading all 12 rows. Every database runs its own calculations, estimates the cost of each possible plan, and picks the cheaper one.

Attention: several simplifications were made in this text to avoid diving too deep into complexity:

- Databases operate in blocks/pages, not individual rows — this has some important implications for query cost calculations.

- Indexes are actually stored in tree-like structures (e.g., B+Trees), not the simple table-like diagrams shown in the illustrations.

- Real-world cost optimizers consider many other factors when calculating plan costs.