Playing with Random Page Cost

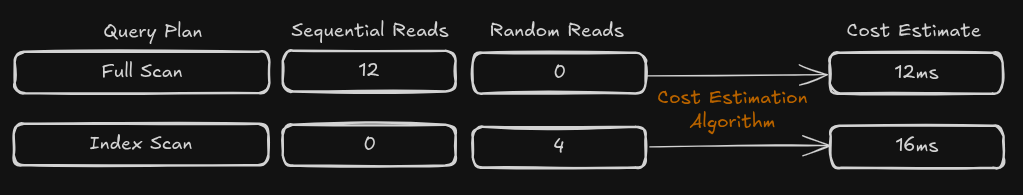

In my previous post, where I explored how databases handle random vs sequential reads, I mentioned Postgres’s random_page_cost parameter. To illustrate the concept, I used the simplified cost estimation below—where, not by coincidence, random I/O is shown as 4× more expensive than sequential reads. That’s because 4 is the default value used by Postgres. In this article, we’ll experiment with this setting to better understand how it influences query planning.

Our playground will look like this: an orders table with 10,000,000 rows and a few key columns—most notably an indexed status column with the following distribution:

| Status | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| AWAITING_DELIVERY | 2,547,518 | 25.4% |

| AWAITING_PAYMENT | 426,870 | 4.2% |

| CANCELLED | 22,552 | 0.2% |

| COMPLETED | 7,003,060 | 70.0% |

For each query that filters by a single status, Postgres has two main options:

- Sequential Scan (Seq Scan): Read the entire table row by row, filtering out the ones that don’t match. The cost of a

Seq Scantends to remain consistent across queries—after all, it always involves reading the entire table. - Index Scan or Bitmap Index Scan: Use the index to find the matching rows, then use

Heap Fetch(orBitmap Heap Scan) to jump to those rows and retrieve their actual data. The cost of using the index varies depending on how many rows match the filter condition. The more matches, the more random I/O operations the database needs to perform

To see this in practice is straightforward. Let’s first filter by CANCELLED, which represents only 0.2% of the table, and then by COMPLETED, which accounts for 70%.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

SELECT * FROM orders WHERE status = 'CANCELLED';

Bitmap Heap Scan on orders (cost=227.44..47607.21 rows=20000 width=34) (actual time=5.049..53.531 rows=22552 loops=1)

Recheck Cond: (status = 'CANCELLED'::text)

Heap Blocks: exact=19915

-> Bitmap Index Scan on idx_orders_status (cost=0.00..222.44 rows=20000 width=0) (actual time=2.140..2.140 rows=22552 loops=1)

Index Cond: (status = 'CANCELLED'::text)

No need to fully understand this query plan for now; the important point is that we’re seeing Bitmap Index Scan on idx_orders_status, meaning Postgres chose to use the index. That sounds like a solid decision, considering 22,552 matching rows is a small slice of the full 10,000,000.

Now let’s see what happens when filtering byCOMPLETED:

1

2

3

4

5

SELECT * FROM orders WHERE status = 'COMPLETED';

Seq Scan on orders (cost=0.00..210971.00 rows=6989667 width=34) (actual time=1.687..540.337 rows=7003060 loops=1)

Filter: (status = 'COMPLETED'::text)

Rows Removed by Filter: 2996940

As expected, Postgres goes with a full Seq Scan, which also makes sense. Fetching 7,003,060 scattered rows via index would mean performing millions of random I/Os—more expensive than reading all 10,000,000 rows sequentially.

Time for action: what plans does Postgres pick when querying each status while we adjust the random_page_cost ?

random_page_cost=4.0

Let’s start with the default: Postgres assumes random reads are 4 times more expensive than sequential ones. Here are the query plans chosen for each status:

| Filter | random_page_cost=4.0 |

|---|---|

| AWAITING_DELIVERY (25.4%) | Bitmap Index Scan |

| AWAITING_PAYMENT (4.2%) | Bitmap Index Scan |

| CANCELLED (0.2%) | Bitmap Index Scan |

| COMPLETED (70.0%) | Seq Scan on orders |

random_page_cost=10

Now let’s tell Postgres that random reads are even more expensive by setting random_page_cost = 10. Here’s how the query plans change:

| Filter | random_page_cost=10.0 | random_page_cost=4.0 |

|---|---|---|

| AWAITING_DELIVERY (25.4%) | Seq Scan on orders | Bitmap Index Scan |

| AWAITING_PAYMENT (4.2%) | Bitmap Index Scan | Bitmap Index Scan |

| CANCELLED (0.2%) | Bitmap Index Scan | Bitmap Index Scan |

| COMPLETED (70.0%) | Seq Scan on orders | Seq Scan on orders |

Analysis of the results:

- For

status = COMPLETED(70%) query, Postgres is now even more convinced that a full table scan is the most efficient option. - For

status = CANCELLED(0.2%) andstatus = AWAITING_PAYMENT(4.2%), it still favors the index. - For

status = AWAITING_DELIVERY(25.4%), however, the increased penalty on random reads made Postgres change its mind: it now opts for aSeq Scan, assuming that randomly fetching ~2.5 million rows is more expensive than reading all 10 million sequentially.

random_page_cost=1.1

Now, time to let Postgres know that no one is using mechanical disks anymore by lowering random_page_cost to 1.1. Here’s what the plans look like now:

| Filter | random_page_cost=1.1 | random_page_cost=10.0 | random_page_cost=4.0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| AWAITING_DELIVERY | Index Scan | Seq Scan on orders | Bitmap Index Scan |

| AWAITING_PAYMENT | Index Scan | Bitmap Index Scan | Bitmap Index Scan |

| CANCELLED | Index Scan | Bitmap Index Scan | Bitmap Index Scan |

| COMPLETED | Seq Scan on orders | Seq Scan on orders | Seq Scan on orders |

Analysis of the results:

- For

status = COMPLETED(70%) query, the change still wasn’t enough to convince Postgres that using the index would be more efficient—it stuck with the sequential scan. - For all other statuses, however, Postgres slightly changed its strategy, switching from a

Bitmap Index Scanto a regularIndex Scan. There’s no need to fully understand what aBitmap Index Scandoes just yet— just that it is a middle ground between a sequential scan and an index scan. That’s enough to understand that Postgres started shifting toward a fully random I/O strategy, in line with the lower random_page_cost we set.

random_page_cost=50

Finally, let’s go full chaos mode and crank random_page_cost up to 50. In this setting, we’re basically telling Postgres that every random I/O is like crossing a river full of alligators. Here are the results:

| Filter | random_page_cost=50 |

|---|---|

| AWAITING_DELIVERY (25.4%) | Seq Scan on orders |

| AWAITING_PAYMENT (4.2%) | Seq Scan on orders |

| CANCELLED (0.2%) | Seq Scan on orders |

| COMPLETED (70.0%) | Seq Scan on orders |

Analysis of the results:

- Alligators are dangerous.

Reality Check

Except in more analytical scenarios, retrieving millions of rows—like we did in our experiments—isn’t that common in real-world applications. So yes, the examples were intentionally simplified for learning purposes.

In practice, queries often include a LIMIT clause. And when they do, the database has a clearer idea of how many rows are needed, making the index path more attractive. After all, fetching a small number of rows through random I/O can be quite efficient if the database knows when to stop.

However, it’s also not that common to see queries with just LIMIT, because in most real-world scenarios, we also want the results ORDERED. And that’s when things start to get interesting again—Postgres now has to explore different execution paths that involve a mix of sequential I/O, random I/O, and sorting strategies. But that’s a topic for a future post.

Conclusion

Hopefully, this little experiment gave you a sense of how important random_page_cost is. As a key input to Postgres’ cost estimation algorithm, it can have a significant impact on the planner’s decisions.